General

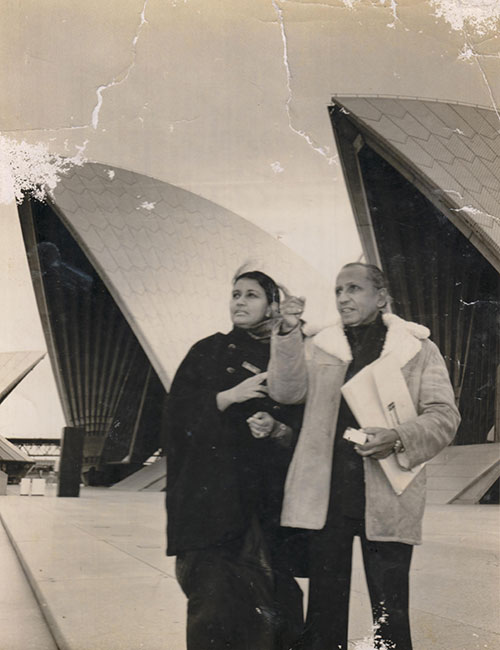

Sumithra peries looking back in nostalgia-By Uditha Devapriya

Source:Island

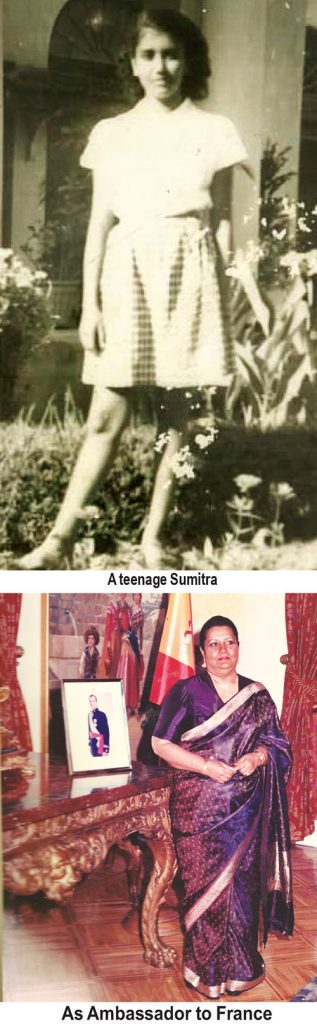

Sri Lanka’s oldest living filmmaker, Sumitra Peries, stands shoulder to shoulder with South Asia’s pioneering woman artist-intellectuals, including her childhood heroine, Minnette de Silva. Yet, barring a comprehensive biography by Vilasnee Tampoe-Hautin, no writer has attempted to locate her life and work in the pantheon of South Asian cinema. A version of this article appeared in Himal Mag Southasia late last month.

The cinema of South Asia blows up in a riot of colour and spectacle, offering a melange of romance, action, and history. Despite its modest scale, this is one of the biggest film industries in the world, worth around 180 billion rupees (roughly 2.4 billion dollars) in India alone. Today, it has transformed into a category of its own, mixing different genres and, at least in India, earning the apt moniker “masala cinema.”

However, while many scholars have written on this industry, few among them seem to have noted its contribution in a rather unlikely front: women’s filmmaking.

Surprising as it may seem, several women made their mark as directors in South Asia. While attempting a chronology is difficult, the first such director is considered to be Fatma Begum. In 1926, when Lillian Gish considered ending her career with D. W. Griffith, and MGM was offering her a six-movie deal, Begum made her first film through her own production house, Fatma Films. Later, in Pakistan, Parveen Rizvi and Shamim Ara made their debuts as directors, while much later, in Bangladesh, Kohinoor Akhter followed suit.

What bound these women together was the way their careers developed. All of them had to transition from acting to directing. It was later, with the onset of a New Wave, in Indian cinema, in the 1980s, that a new generation of filmmakers, among them Mira Nair and Deepa Mehta, took centre stage. The only notable exception to this trend, who continues to stand out, is to be found outside India.

Long orientalised for its sandy beaches and mist-clad mountains, Sri Lanka boasts of an obscure but vibrant cinema. Though dominated by men, women, too, have made their mark in it, and not just in acting. Among them, one name stands out: Sumitra Peries, the country’s oldest living filmmaker.

Sumitra Peries was born Sumitra Gunawardena on March 24, 1935, in the village of Payagala, 40 miles from the island’s capital, Colombo. Her mother hailed from a wealthy family of arrack distillers, her father from a household of fervent political radicals.

While Sumitra’s paternal grandfather had participated in the resistance against colonial authorities, two of her uncles became leading socialist politicians in British Ceylon. One of them, Philip, whose association with Marxism had taken him to far-flung places, such as the Pyrenees during the Spanish Civil War, went on to dominate the political stage in the country.

By contrast her father, a Proctor, had not been as politically inclined: barring one unsuccessful attempt to get into the country’s State Council in 1936, his career was largely overshadowed by his brothers. Nevertheless, Sumitra recalls, “our home in Boralugoda was open to radical politicians. They made it their lunch stop and rest-house.”

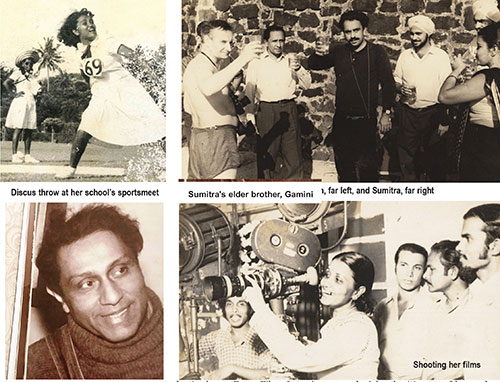

After she turned 13, in 1948, when Sri Lanka gained independence from the British, her family decided to move to Colombo. She transferred from a Catholic school, St Mary’s College, in her paternal village of Avissawella, to Visakha Vidyalaya, Sri Lanka’s leading Buddhist girls’ school. The first photograph of her in the press shows a girl throwing a discus at a sportsmeet at Visakha, exuding a youthful, defiant ardour.

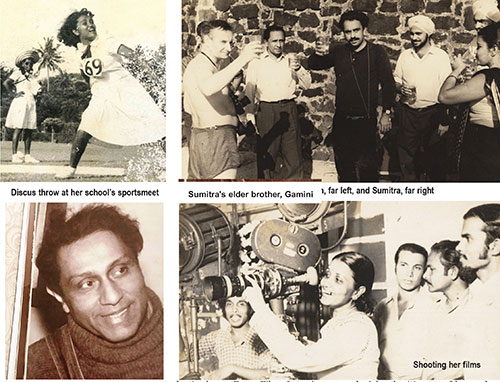

Two years later, her mother passed away. Devastated by the loss, her elder brother, Gamini, left the country. Sumitra recalls how, a few years later, he asked her to join him in Europe. “I agreed at once. In 1956, I got aboard a P&O liner and set sail to the Mediterranean, all on my own.” She was not quite 21.

Arriving in Naples, Sumitra met Gamini and went to Malta. “He had a yacht docked there, and was leading a rather bohemian life with some friends.”

Over the next six months, Sumitra, Gamini, and their friends “sailed along the Italian and French coasts, savouring the Mediterranean.” At Saint-Tropez, she happened to see Brigitte Bardot and Roger Vadim making And God Created Woman. Her first sight of a movie set intrigued her greatly.

“I didn’t know what to do next. We decided on settling in Lausanne. My brother returned to Sri Lanka, leaving me behind in a world far from home.”

Lausanne failed to grow on her: “I longed to see France, on the other side.” A train and cab ride later, she was in Paris, “without a penny in my purse.”

On family instructions, she was soon boarded at the Ceylon Legation. There she met a man who was to change the course of the Sri Lankan cinema – with a significant, if underrated, contribution from her.

This was Lester James Peries, widely regarded as Sri Lanka’s pre-eminent filmmaker, and before long, her husband.

Lester proposed to Sumitra that she go to England. She agreed, enrolling at the London School of Film Technique. Founded in 1956, the LSFT was located in a suburb in Brixton. Less tempestuous than the Mediterranean, it offered Sumitra a more stable home.

Among her lecturers and peers at the School, she remembers Lindsay Anderson the most. Over time, the two of them got to know each other well. “He knew Lester long before he met me. The three of us became very good friends.”

Sumitra excelled in her studies, but finding a job in London was not easy for her. Only after knocking on the doors of Elizabeth Mai-Harris, one of Britain’s leading subtitling firms, was she offered work in the industry. “My fluency in French helped,” she remembers.

After a while, however, she longed to be back home. On Gamini’s advice, she returned to Sri Lanka, ending up as the only female crew member aboard Lester Peries’s second film, Sandesaya (The Message, 1960). Four years later they married, and remained together until Lester’s death in 2018.

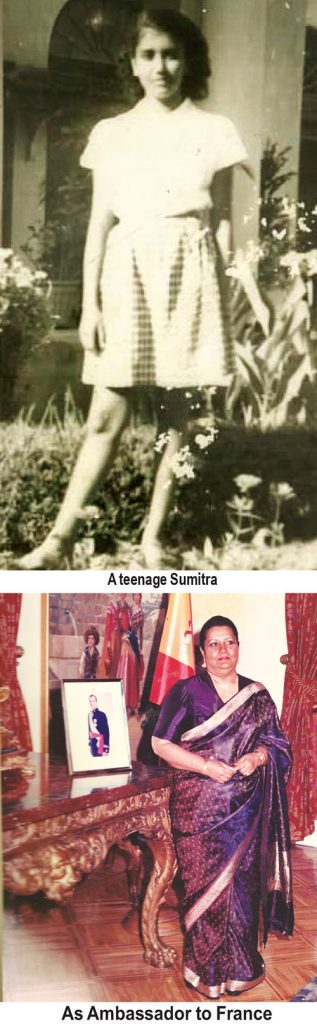

In 1964, Sumitra began editing films. More than a decade later, in 1978, she ventured into directing with Gehenu Lamayi (Girls), following it up with eight more films, including her most recent, Vaishnavi (The Goddess), in 2018. She would go on to serve in other capacities as well, prominently as Ambassador Extraordinary and Plenipotentiary for France and Spain from 1995 to 1999.

The essential themes of Sumitra’s work are in Gehenu Lamayi: the innocence of childhood, the burdens of women in patriarchal society, the rift between rich and poor, the torments of adolescent love. Lacking the song-and-dance sequences of South Asian blockbusters, her films are sharp, often searing, in their critique of male chauvinism.

Sumitra’s aesthetic sensibility is distinct: according to British filmmaker Mark Cousins, “she uses zooms like Robert Altman, probing shyness and tentative love.” Sumitra herself seems to be aware of a certain quality of meticulousness in her work: “I often get an urge to recompose the mise-en-scène, even to prettify it. I think that shows in the final product.” For Cousins, that reveals “what a great visual thinker she is.”

By Sumitra’s own confession, her attitude to women was shaped by the women who figured in her life, including her mother. When asked about the films she likes, she at once mentions Carl Theodor Dreyer’s The Passion of Joan of Arc. “I remember seeing Renée Falconetti’s face and being enthralled by it. I could never forget that face. It came back to me, many times in fact, when I started directing films.”

Despite the high praise she has won, however, she has also received scathing criticism. Some critics have labelled her work as “feminine” and accused her of not being sufficiently “feminist”, because of the way in which her female characters succumb to their plight – such as when Kusum from Gehenu Lamayi bitterly accepts a life of loveless poverty as her “fate.” Thus, the authors of Profiling Sri Lankan Cinema conclude that she “has not gone far enough as a director with feminist intentions.”

Sumitra’s response to these criticisms is that she can portray women “as someone other than who they are only by manipulating the story.” In the few instances when she in fact attempts this – as in Yahalu Yeheli (Boyfriends and Girlfriends, 1982), where the heroine disobeys her father, a landlord, and joins some villagers protesting his hold over them – one notices a tinge of artificiality. Overall, however, she sticks to a realist principle: “I prefer to depict women as they are, rather than who they should be.”

Today Sumitra resides in Mirihana, a quiet suburb located about six miles from the capital. She and her husband spent their married life in Colombo, in a house along a road that bears his name. Yet following his death, owing to certain unfortunate circumstances involving the legal title to their residence, she had to vacate her premises. She hasn’t come to regret the shift: “It’s much quieter here, in tune with my sensibility.”

Still active and working on her next project, at 87 Sumitra remains open to the possibilities of her medium. It goes without saying that her work stands out in the world of South Asian cinema. While being utterly modest about her achievements, she admitted one thing the last time I met her: “I rebelled against the idea of what a woman had to be in my society, as a girl and a director. In the end, despite those strictures, I prevailed.”

The writer can be reached at [email protected]