General

Sri Lankan Gullivers facing Cricketing Goliaths in 1975

Source:Thuppahis

Nicholas Brookes, in The Cricket Monthly, …. where the title is “Brave As Loons, Poor as Mice,” …. with highlighting emphasis inserted by The Editor, Thuppahi

In 1975 the Sri Lankan cricket team had never toured outside Asia. But those who’d been paying attention would have known that their inclusion as one of the eight teams competing in the World Cup that year was well earned. In the past 18 months they’d dismissed West Indies for 119, fallen 17 runs short of victory in Pakistan and had the better of a drawn game against India.

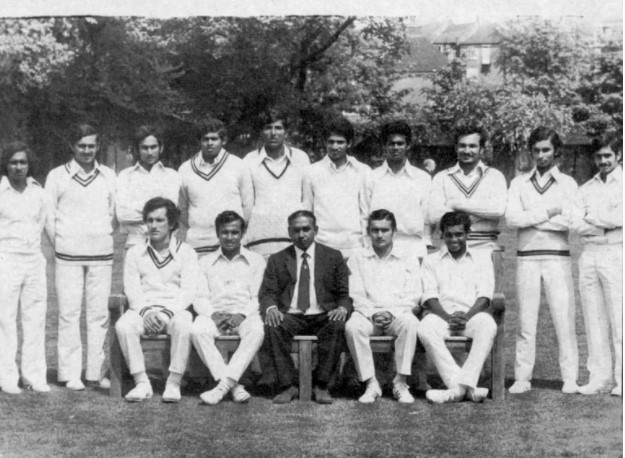

Standing L-to R: Dulep Mendis, Lalith Kaluperuma, Sunil Wettimuny, Tony Opatha, HSM Pieris, DLS De silva, Ds De silva,Dennis Chanmugam, Anura Ranasinghe, Bandula Warnapura, ……..

Seated L to R: David Heyn, Anura Tennekoon (captain), KMT Perera (manager) Michael Tissera, Ranjit Fernando.

Pix derived from The Prudential Cup Review by Gordon Ross, page 9.

The one-day game posed a new set of challenges – Sri Lanka had only played nine limited-overs matches in their history – but the squad was blessed with a cast of players naturally suited to short-form cricket. What’s more, the World Cup offered a rare opportunity for them to show what they could do. Perform well and it might prove a stepping stone towards Test status. A seat at cricket’s top table beckoned.

The Board of Cricket for Sri Lanka realised what was at stake and decided to arrange a two-week pre-tournament trip to an army camp in the hill country town of Nuwara Eliya . For the players – used to sneaking in an hour’s practice between the end of work and the six o’clock sunset – this was a welcome novelty.

The journey to their temporary base took the best part of ten hours. When the coach broke down en route, players had to get out and push. Notwithstanding Nuwara Eliya’s remoteness, it seemed the ideal place to prepare for the challenges ahead. High in the misty hills, clouds hang low and the air is often chilly. Sri Lankans fondly refer to the town as “Little England” – it was as close as they could get to replicating the alien English conditions.

But the ground at Radella where they practised was far from perfect. The wicket was slow and stolid, the boundaries tiny. After days of gleefully smashing sixes into the surrounding tea plantations, some of the lower-order batsmen began to think facing Dennis Lillee and Jeff Thomson might be a doddle.

The board also saw fit to recruit a trainer for the team. Wickramasinghe was an Air Force officer by trade: he took to running the side into the ground with all the grim sadism of a drill sergeant. They were up at six each morning for circuits around the racecourse, then back to the camp for cold showers before training. “There was only one tap,” recalls wicket-keeper and opening batsman Ranjit Fernando. “All of us used to go there to bathe. It was severely cold.” A hot-water line was finally installed when some of the players started getting sick.

It was not ideal preparation, but the team left the camp fitter than when they had arrived. And they managed to find time for a tour of the – a trip one or two enjoyed more than they should have. Still, they deserved to let their hair down. It had been a tough fortnight’s training, and hanging on the horizon was some of the hardest cricket they would ever play.

***

Rain swirled around west London as the Air Lanka flight touched down on the tarmac at Heathrow. The players were underwhelmed by their first glimpse of an English summer. Some were surprised when they boarded their bus and saw a white man behind the wheel, others taken aback by the sprawling scale of the city. All were shocked when they arrived at their lodgings in Bayswater.

Sri Lanka’s cricketers understood that their board survived on a shoestring budget. None expected a red carpet rolled out for them, but they weren’t fully prepared for the disaster that was the Ceylon Student Centre. The building was soon to be condemned. The rooms were like dungeons, blankets were threadbare. As in Nuwara Eliya, there was no hot water. Seamer Dennis Chanmugam was in the bathroom when a section of the ceiling collapsed on his head. “The facilities were terrible, but we couldn’t complain,” reflects former captain Michael Tissera . “We had no money. And we had the opportunity to play in a World Cup in England, so why grumble? In the end it was all good fun.”

There were some bright spots too. “The food was very good. Good rice and curry,” recalls David Heyn, a left-handed batsman noted for his fielding in the covers . And in the lobby there was a TV – a device not introduced to Sri Lanka until 1979. One evening the players were sat around when rain started spurting through the roof onto the set. They found a bucket, placed it on the TV’s hood and continued watching. This was a group that took all in their stride.

Having arrived in London three weeks before the start of the tournament, there was plenty of time to acclimatise. In the absence of proper training facilities, the players organised impromptu sessions in public parks. The board, unable to budget for meals, had arranged for them to attend endless functions where food would be provided. But this meant trekking all over town, which quickly became a distraction. They had come to play cricket.

And there was plenty to be played. During their first week Sri Lanka had five warm-up matches. The opposition, largely club sides, put up little resistance. There were nonetheless hurdles to overcome. “At times, the cold was unbearable,” remembers future captain Duleep Mendis. It was aggravated by the fact that the board had been late ordering cricket jumpers; the team had to do without during their first game against Hampstead. They arrived on the morning of Sri Lanka’s second match. Still, players found that balls hit hard could sting the hands. “Some of us didn’t even know how to stretch,” explains Tissera. “The climate is so different. It posed a lot of challenges.”

Of course, there were novelties too. The team were happy to be in London – and after thrashing Finchley, they took a trip to the cinema in Piccadilly Circus. But they hadn’t realised it was the eve of an England-Scotland clash at Wembley; football fans swarmed the streets, transforming central London into a carnival. The scene was so raucous that black cabs decided to give potential passengers a wide berth. The players couldn’t catch a lift no matter what they tried. Eventually 12 of them had to pile into a single car back to Bayswater.

***

Things took a turn for the better once tournament sponsors Prudential took over. The team was shifted to the Kensington Close Hotel, two miles and a world away from the Ceylon Student Centre. Competition also stepped up a notch. Although Sri Lanka lost two practice matches against New Zealand in Eastbourne, there were positives to take from both. Ranjit Fernando made a classy unbeaten 98 in the first; in the second, the team was going well in its chase until 18-year-old Anura Ranasinghe was bizarrely run out. Comfortably home in his crease, he jumped to avoid being struck by a throw from the field. The ball clattered into the stumps and he was given out by the umpire. Sri Lanka’s fans, sat in their parked cars around the ground, began to honk their horns. The noise rose into a cacophony: the game had to be stopped until silence was eventually restored.

ALL the cricketing men assembled at lunch at the Lord’s Cricket Ground

One final pleasantry had to be performed before the tournament could begin: a presentation at Buckingham Palace followed by an official lunch at Lord’s. The Royals wandered around amiably chatting. Of course, the players had not been briefed on protocol, and David Heyn tried to strike up conversation with the Queen by asking her a question. He was greeted with stony silence. But the team enjoyed every minute of the experience. “To visit a place like Buckingham Palace was a dream come true,” reflects captain Anura Tennekoon.

That dream quickly turned into a nightmare when Sri Lanka’s World Cup got underway against West Indies the following morning. The players arrived at Old Trafford to find the ground enveloped in low-hanging cloud. Clive Lloyd won the toss and elected to field; the combination of gloomy skies and a green wicket enabled Bernard Julien to do things with the ball the Sri Lankan batsmen had rarely seen. “He was moving it in the air and off the pitch,” remembers Tennekoon. “We couldn’t counter it.” The team batted less than 38 of their allotted 60 overs, scoring only 86.

In reply, West Indies lost just Roy Fredericks as they cantered towards their target. “It was over by lunchtime,” recalls off-spinner Lalith Kaluperuma. To add insult to injury, a busload of Sri Lankan fans had been delayed and now they arrived as the game was petering out. The crowd continued to swell, but there was no cricket to entertain them. . “By playing that, we were totally demoralised,” says Fernando. “Thoroughly dejected,” agrees Mendis. “But Australia was another game and everyone was keen to play better.”

***

The team travelled back to London with fire in their belly. But they were dealt a blow on the eve of their second match. David Heyn – without doubt the side’s best fielder – arrived back at the team hotel 15 minutes after curfew. He was promptly suspended. Sri Lanka were not the most athletic outfit, so this was a loss they could little afford.

Fielding first, they had to work hard as Australia made the most of a true Oval wicket. With the boundaries pushed back to the fence, batsmen were able to run four on several occasions. Having raced away to 182 for 0, they eventually reached 328 for 5. Sri Lanka would not die wondering. Fernando bludgeoned Lillee for three boundaries in his first over, including a glorious cut over the waiting slip cordon. He and Bandula Warnapura went, but Sunil Wettimuny and Mendis steadied the ship. After 31 overs, the scoreboard read 150 for 2. The chase was on course.

Australia captain Ian Chappell would later describe the match as “haunting”. Since arriving in England, his team had been hounded by the press over their persistent short-pitched bowling. Chappell saw the game against Sri Lanka as a perfect PR opportunity. He instructed his bowlers to pitch the ball up. But by this stage he’d seen more than enough dashing drives for one day. Chappell threw the ball to Jeff Thomson. Captain and bowler’s minds were in perfect harmony. It was time to see if the Sri Lankans could play off the back foot.

In 1975 Thomson was at his zenith. None of the batsmen who played in this game hesitate to describe him as the fastest they faced. All agree the challenge was compounded by his slingy, round-arm action. “He came in like a javelin thrower, so you had no idea what to expect,” explains Tissera. “Because of the action, you picked it late,” agrees Tennekoon. In those days, with no helmets or chest guards, that was a daunting prospect.

Standing at the non-striker’s end, Duleep Mendis had a more visceral reaction. “Watching Thommo’s thunderbolts at 100-plus mph was no joke. Marsh was collecting his deliveries over head height almost another 22 yards back.” Nonetheless, Mendis was without fear. When Thomson bowled short outside the off stump, he tried to take him on. His bat found only fresh air. The next ball pitched in the same spot; Mendis attempted the same stroke. But the ball cut back off the wicket and went crashing into his forehead. He crumpled in a heap. The crack, like a gunshot, was sickening. Horrifically, the ball raced off towards the cover boundary.

There was no stretcher at the ground, so teammates Mevan Pieris and Dennis Chanmugam rushed to the middle to carry Mendis away. “His eyeballs were turning,” remembers Pieris. “He was in a very bad way. But he had the strength to put his arm around me, I could feel him holding on.” Mendis says he was “fully unconscious… I came back to my senses only when I was being carried off the field. When I woke up the next day, it was like I was carrying 100kg on my head.”

Tennekoon had seen the incident from the other end and escorted Mendis to the dressing-room, so it was a good ten minutes before he made his way to the crease. The crowd might have thought Tennekoon he wasn’t coming at all. Some booed the bullying Thomson, but he remained unperturbed. Wettimuny was made to wear a couple around the in his , before Thomson sent a vicious yorker hurtling into the big toe of heel of As Wettimuny hopped around in agony, the bowler threw his stumps down. None of his teammates joined the appeal, but he remained remorseless. “It’s not broken, but if you face the next ball, it bloody well will be,” Thomson told the wincing batsman. He was true to his word. The next ball cannoned into the identical spot. Wettimuny could take no more. He hobbled halfway to the boundary rope, before he too had to be helped from the field.

The fallen pair were taken to St Thomas’ Hospital. Wettimuny had a broken foot, a cracked rib and a badly bruised body; by some miracle, Mendis suffered no serious damage to brain or skull. While Wettimuny was lain up, a policeman began asking questions. “Who hit you?” “Thomson,” he replied. “Where?” “At the Oval.” “What were you doing?” “Playing cricket.” Still the constable was unable to join the dots. He looked stern. “Do you wish to press charges?”

With two of their batsmen in hospital, Sri Lanka could easily have wilted. But Tennekoon and Tissera batted bravely, standing up to the attack to make 48 and 52 respectively. The team ultimately fell 52 runs short of their target, but the 276 they scored remained a World Cup record for a side batting second through to 1983.

What’s more, they had shown the world they possessed skill and spirit in abundance. After the match, the Australians invited them for a drink in their dressing-room. “I think they felt a little bad about sending two of our guys to hospital,” Tennekoon reflects. But it was more than guilt. Down to a man, the Australians knew they had been given a hell of a game. This was a performance Sri Lanka could be proud of.

***

It was disappointing, then, that they limped out of the tournament against Pakistan. Zaheer Abbas played a gem of an innings; in reply, Sri Lanka’s batsmen never got going. In many ways, this was more disheartening than the West Indies defeat. The track was good for batting, the foes familiar. But on the day, it just didn’t happen.

Though the team’s results were mixed, there were several mitigating factors. They had no knowledge of English conditions and little experience of limited-overs cricket. Few would disagree that their group contained the tournament’s three best sides. And the lack of a support team was undoubtedly costly. Sri Lanka had no coach, physio or trainer. Had they been able to hire an English pro who was familiar with the format and conditions, it would have been a great help. But there was no money. The players had to figure things out for themselves.

While their tournament might have been over, the tour was not. One man Sri Lanka could count on was Dusty Miller. Ahead of the World Cup, he took the team to the shop of ex-Middlesex and Glamorgan spinner Len Muncer and told them each to choose a bat. And more crucially, he organised and funded a post-tournament trip to Holland and Denmark.

It may seem unfathomable today, but the Dutch and Danish were up in arms about Sri Lanka’s inclusion at the World Cup. Both thought that they were superior sides; Dusty’s trip was a chance to prove them wrong. So after comfortably beating East Africa at Taunton, the team boarded a ferry to Brussels. David Heyn celebrated his 30th birthday on the boat; three days later in The Hague he smashed a breakneck 73 not out to ensure victory against Netherlands inside two days. Much to their displeasure, the Danish were dispatched with equal ease.

In typical Scandinavian style, an enticing smorgasbord had been laid out for the post-match tea. But while the Sri Lankans gazed longingly at the table adorned with lager, sandwiches and sweets, Denmark’s captain could be heard castigating his team in their dressing-room. For 15, 20, 25 minutes the visitors waited. After half an hour they had little choice but to leave. The team returned to England. The spread remained untouched. Perhaps the lecture still rolls on.

***

When it was time to fly back to Colombo, more than half the squad were missing. Six had earned contracts to play league cricket in England. This was groundbreaking. Every member of this side stresses the fact that they played purely because they loved the game. They had to: at this stage, being a cricketer in Sri Lanka meant making a real financial sacrifice. There was no money to be made – players had to hold down full-time jobs to support their careers. Michael Tissera even had to take his annual leave in order to play in the World Cup.

The discovery that cricket could offer financial opportunities was a genuine surprise. “It was life-changing for a lot of us – and not just for the guys who stayed, but for guys who came after,” explains Heyn, who would emigrate to England in 1976 once it became clear the ICC would not immediately award Sri Lanka full membership. “A precedent was set. You could go to England and make a little money. It opened people’s eyes.”

Over the course of six weeks, this group of cricketers learnt a lot. But they also showed the world a few things. Many had thought they were coming to make up the numbers; instead, they proved that on their day they could hang with the best of them. From this point on, the path to Test status was clear.

Forty-four years later, the squad’s cricketing days are well behind them. What remains is friendship. Sri Lanka’s cricketing circle in the 1970s was small, centred around a few Colombo schools and clubs. These guys had spent their lives playing together; to hear them laugh as they reminisce about the summer of ’75 is to understand the kind of brotherly bond that sport can create. They made plenty of new friends too.

One morning last year, Duleep Mendis – now coach of Oman – was sat in his apartment in Muscat. The phone rang. Without introduction, the caller launched into a tirade. “Pad up. And wear your bloody helmet and come to the nets. I want to blow your head off.” Mendis recognised the voice straight away. It was unmistakably Thomson.

***********

SOME PERTINENT PICTURES